Home

Dec 01

2020

2 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

The Christmas after our divorce, back in 1992, was a time I, and I am sure all of us, dreaded. My father had died that year, the boys were with their Dad, and I was waking up on Christmas Day alone for the first time in my whole life, aged 42. I was seeing family for lunch but Christmas morning had always been a time surrounded by family – my parents and siblings for the first 21 years of my life and then husband, kids and Christmas stockings in adulthood. I wondered how I would sustain myself that morning on my own.

In the end it turned out to be a rather mystical experience. I made a good breakfast for myself and then took myself into the sitting room and sat beneath my beautiful Christmas tree, with Vivaldi’s Gloria playing on the CD player. I just sat there for a while, quietly listening to the music and letting my eyes go into gentle focus on the tree and its lights. Everything seemed to become a little magical and I felt held by the tree, the music, and the presents I then opened from my friends. I have never forgotten how a moment I dreaded actually became one of the most spiritual experiences of my life, where I felt connected and at one with everything.

It makes me think about how life can surprise us sometimes, and how, in these lockdown days of Coronavirus, we need to find ways to take ourselves out of the worry and into the now, to music, to nature, to the beauty all around us that we so often take for granted. I still occasionally pretend I am a tourist visiting London for the first time and am always delighted and taken aback with its architecture and elegance, the parks, gardens, landmarks. Wherever you are, this can be an uplifting experience and you can also take in the trees, birds, the crunch of the leaves on the pavements, the joy of children jumping in puddles as children have over the generations. Watch children come out of school at the end of a day, sense their excitement about Christmas or a tooth fairy: it’s infectious.

It’s about opening our eyes to the richness of those things around us. It can be fun to walk about our home in a similar way – not as if we are seeing it for the first time but that we are remembering where we bought a painting, where we read a book, when we bought a piece of furniture, with whom. It’s about remembering the fun and treasured memories of our life, the pottery a son made when he was 8, a letter a daughter wrote to you aged 5, a picture painted by a grandchild. It’s about taking time to stop, remember, appreciate yourself and all those experiences.

When we are alone, or feeling down, it’s too easy to forget all the things one has achieved, small or large, in one’s life. In our creative writing course we are encouraged to take a piece of paper and spend 10 minutes writing down things we feel proud of, or happy memories, or places we have seen. And the friends and family who have been and may hopefully remain a part of our lives.

Music is so important, I find. Listening to Portuguese Fado makes me cry – that’s helpful, as I don’t find it easy to cry and it can spark off the tears that needed to flow about something. Listening to country and western makes me smile and dance – probably me at my happiest! I don’t think my sister will mind me sharing that she listens to the Beatles and it reminds her of the happy times of her life with a friend in Paris, then with her late husband, Leo, those carefree moments of youth, and she feels younger, more agile, the years of age slip away. The delightful thing is my daughter-in-law shares this enjoyment and I have just handed over to her a suitcase full of my Beatles memorabilia (I was a Beatle-maniac!). Lovely to have it appreciated!

Some spiritual teachers might say this kind of practice feeds the ego but I think we need a little ego, just not too much. Nothing would get done in the world without some ego. It’s easy to sit on a mountain top and meditate away one’s ego, far harder to do so in the real world! In the real world we have to earn money, find something fulfilling to do, make our lives meaningful in some way, and still do the chores. But we do have to manage our egos, that’s for sure. It doesn’t help the world if we all become boastful, like President Trump!

And so, I believe we can find a place inside us where that ego feels in harmony with oneself and the world outside, where it is quiet but steady, with a feeling of contentment and a feeling that we belong in this world around us and feel at one with it, which was the state I reached sitting under my Christmas tree that morning back in 1992.

I feel our spiritual leaders have been woefully silent during this coronavirus pandemic. They could have given people so many words of comfort but I have heard few. They could have reminded people about gratitude, which helps us so much to notice what we can appreciate in our lives, who does sustain us, who is there for us. They could have reminded people about forgiveness, as resentment only eats away at the person holding the resentment when the person who did the deed might be living a life blissfully unaware of the hurt they caused. They could have reminded us of kindness, and how when we carry out an act of kindness we are also being kind to ourselves. They could have reminded us of trust, trust that “this too will pass” and, where we have little control, then to do what we can but trust that life has good times and bad, always has and always will, and hopefully good times will return.

So whether you are about to spend Christmas alone, or in a different way this year, or are perhaps someone who doesn’t celebrate Christmas but does, nonetheless, usually get together with family or friends over this holiday period, slow down your senses, open your eyes to the outside beauty of the world and, at the same time, connect with that quiet inner self deep within and find some peace and sustenance.

Wishing you well…

Nov 12

2020

2 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

It’s 100 hundred years since Sir Frederick Banting and his laboratory team discovered insulin and we began to understand how it interacts in the body. I knew nothing about Diabetes Type 1 until my bright and beautiful granddaughter Emmeline was diagnosed with it aged 8. It came out of the blue and presented a steep learning curve for her, my son and his wife, and for me as a granny.

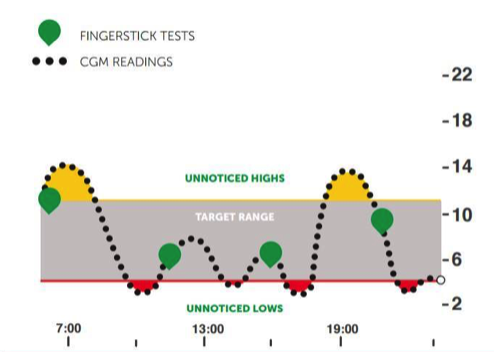

Emmeline, like many other children living with Type 1, is stoical and determined to live her life in the way her other friends do. Nevertheless, the reality is that her life has been changed by the diagnosis and that she and her parents have to be aware of the level of her blood glucose 24/7. Keeping her, and the other approximately 29,000 children living with Type 1, within normal blood glucose range takes time and attention.

Her childhood cannot be the same as another child’s as she has to weigh and measure everything that she eats, including any sweetened or fizzy drinks, calculate the carbohydrate content, and adjust the measurement of insulin accordingly. When she comes to stay, I have to get with the programme in terms of weighing and measuring and monitoring everything to keep her well. Attention continues into the night, as her levels can raise or dip, and need correction, whatever the hour. She has to carry her emergency bag of glucose and syringe with her at all times in case of hypos.

But life for today’s children is vastly improved from the days when a prototype insulin pump was as large as a backpack. Nowadays an insulin pump will fit into a pocket, like a small mobile phone. And continuous monitoring is available through technology that keeps check of levels and sends them to a parent’s smartphone so that the parent can be in a business meeting many miles away but can alert the child and their school that a correction needs to be made, or a glucose pill swallowed, to rebalance the level.

And my granddaughter has received brilliant and world-class support from St Mary’s Paddington and the Hammersmith Hospital and JDRF (Junior Diabetes Research Fund) provide a resource of emotional support and information, as well as being the largest non-profit organisation carrying out research into Type 1, its causes, symptoms and treatments. Their aim is to create a world where Type 1 no longer exists through discovering how to prevent it.

But for now it is not preventable. There are many misunderstandings about diabetes and the key is the difference between Type 1 and Type 2. Type 2 is a lifestyle problem. Type 1 is an auto-immune disease. This means that it is not due to a child eating the wrong thing or living an unhealthy lifestyle. It is due to that child or person’s immune system malfunctioning to attack and destroy the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. Insulin is crucial to life and needs to be managed carefully as otherwise it puts pressures on various areas of the body such as the brain, kidneys, eyes and nervous system. The management of insulin levels has vastly improved the risks.

I wish the media would be more careful in their reporting of statistics around diabetes, as they often lump both Types together and do not make the distinction between Type 1 and 2 in their reporting. It is this laziness that perpetuates many of the myths around Type 1 and it’s time they became more knowledgeable about the difference.

The symptoms are significant thirst, needing to go to the loo often, and fatigue. It takes a parent being on top of this to notice, google and take the child to the doctor. They often require hospital treatment to rebalance and start the process of finger-pricking, injections and monitoring to achieve normal range levels.

Although today’s technology means that a child’s life is less disturbed than they used to be, there is, nonetheless, a process of loss, both for the child and their parents and, I would say, for the grandparents. I have personally found it inspiring to watch the courage and fortitude of Emmeline in managing her life with its new preoccupations, and also watching the tender and attentive care of her Mum and Dad in ensuring she has all she needs to keep her well. And, of course, one has to also remember those with other conditions, who are worse off, and those with Type 1 in other parts of the world who do not have the marvellous support my granddaughter has.

JDRF and other organisations and labs are doing amazing research to try to (a) prevent Type 1 and (b) treat it. They talk of developing an artificial pancreas, as the pancreas basically stops functioning with Type 1. I read yesterday of a student at the University of Huddersfield, Tyra Koslow, who has invented a blood glucose monitor for managing type 1 that can be contained within a futuristic-looking earring that resembles a tiny Bluetooth earpiece. It requires only a normal ear piercing and can pass radio waves through the earlobe to monitor the user’s blood. I am sure that during Emmeline’s lifetime there will be some amazing progress in technology.

In the meantime, those living with Type 1 will find that even if they do the same thing each day, or eat the same food, their levels are likely to be unpredictable. They vary according to weather, exercise, temperature, and stress. Hormones impact levels so there are variations when going through puberty, or, for girls, pre-menstrual or menstrual, as oestrogen levels make the body resistant to insulin. It can be difficult to control the levels perfectly, for sure, and as a child grows their body and hormones change, so managing the levels is a continuous adjustment according to their needs.

You may know people with Type 1 and not realise they have it, nor understand the demands it places on children, parents and adults to manage their health. Frank Gardner, the journalist who was disabled by a terrorist bomb, has said on television recently “what people don’t see is all the stuff that we have to deal with beneath the surface”. He describes it as the ‘iceberg’. You only see what is shown above the surface in Type 1 but below the surface there will be fingerpricks, injections, input of carbs and calculations, changes of monitor and pump sites.

Happily now there are people in the public sphere talking of their experience – ex-Prime Minister Theresa May, James Norton the actor, Sheku Kanneh-Mason, the cellist who played at Prince Harry and Meghan’s wedding, all of whom have the condition.

And so I shall be celebrating World Diabetes Day today in honour of my beautiful and courageous granddaughter, of whom I am incredibly proud. To show solidarity, on Saturday 14 November, people are being asked to wear blue nail varnish and post photos to raise awareness, so this is what I am doing!

And if any of you feel like giving any small amount to my Just Giving page for JDRF (Junior Diabetes Research Fund) then of course I shall be thrilled, as every pound or penny helps towards their fantastic research.

But either way, the main thing is to bring you some of the awareness of this condition, of which I knew nothing before Emmeline’s diagnosis in 2019.

Oct 26

2020

2 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

Winter is coming. We need to bolster ourselves up individually, and as a country, to withstand the challenges we face as a result of the Covid pandemic. We need to rise above party politics, race, gender and culture to work together to turn our lives and the economy round. It is in all of our interests to believe in ourselves and the UK. That is not a nationalistic or populist statement. It is common sense. It is about being grateful for the environment in which we live. It is about noticing what we have in common rather than what divides us, for a divided country is an unhappy country. It is about gathering together to get ourselves out of this mess.

I am so fed up with the endless rhetoric emphasising our failures and divisions. How does it help any one of us to stress this rather than to draw us together as a group? News presenters seem to delight in highlighting bad news, where the government has got something wrong, or where they can catch out some politician or spokesperson. There is a sense of “gotcha” pleasure – but where does it get us? Perhaps they think it will keep their audiences this way. Personally, I am not so sure.

I heard someone say recently that “if you create a villain, you start a war.” With identity politics, race, gender and culture wars we have created far too many perceived villains and are starting far too many wars between us all, that serve little purpose other than to make everyone unhappy.

And unhappiness has consequences. I have heard of three suicides and an attempted suicide in the last six weeks. It is totally irresponsible for people of power and influence to be so negative about the UK. The success of this country benefits every single person who lives here, rich or poor.

There are constructive ways of analysing and articulating solutions. Pointing fingers at politicians, scientists, business leaders or others will not get us out of our current problems. Analysis is productive, negativity is not. Waiting and expecting all the answers to come from politicians, scientists or others will not bring about any magical solutions. It is up to us, you, me and every individual in this country to begin to regain a little pride in what it is like to live here, to notice the beauty of the countryside, appreciate the history, culture, architecture, science, innovation, the arts. You are likely to feel happier as a result and we are far more likely to pull ourselves out of this hole faster if we let go of the tendency to push those with different opinions away, and start to work together.

Matthew Syed in his article on ecosystems in The Sunday Times this week writes of how a lifetime of observing one ant in a colony would tell you nothing, whereas seeing the colony as a coherent organism that solves problems, demonstrates their powers of problem-solving, building methods of housing, and feeding the group. He argues that this is the secret of our species too, for the way we create progress is through the complex interplay of people and institutions. The individual plays a part but it is their interaction with others in their community that achieves change. Working together is a survival mechanism, for “when we curtail our sociality, we curtail our humanity” and, I would add, our innovation.

Are we really as bad as the media and the chattering classes like to make out? After all, where is the country that gets everything absolutely right? There isn’t one. Every nation and culture has made mistakes in their past and continues to do so. That’s life. There’s much criticism of Western values and the way we live here but quite honestly I am horrified by how women are treated in many other areas of the world. We have fought hard for equality of gender, race, sexual preference and creed and we need to hold on to these rights. We do not want to walk mindlessly into a world that takes us backwards, by allowing the endless criticism of the way of life here in the UK to blind us to what we have achieved.

Of course, mistakes have been made over Covid-19 but the situation is far too complex to be able to say with any certainty yet which countries actually got things right over Covid. Whether Labour, LibDem or Conservatives were in power the fact is they would all be getting some things wrong. Politicians around the world have their weaknesses and right now I wouldn’t want to be any one of them, of any party, anywhere. Countries who locked down early and insisted on masks have nonetheless got second waves too. We know also that there are other countries who, if given a referendum, could well vote to exit the EU. It is not specifically a British perspective. There are plenty of other countries that have issues over race. Kemi Badenoch observed that she thought the UK was one of the better countries regarding racial tolerance. The French-Tunisian comedian Samia Orosemane commented recently that audiences in the UK are more open-minded than in France. Let’s consider that.

Personally I have travelled to many countries and believe that whilst our democracy and its institutions are not perfect they actually work reasonably well – or did before Covid knocked everything for six. If it were really so bad why would so many people want to come and live here? Could it be that people who report being happier in other countries enjoy a media who are not so consistently negative and critical of everything that happens within that country?

We face a rocky road ahead and a competitive one. I read that Chinese millennials today are feeling confident, assertive and proud of their country. We can’t afford to allow ourselves to fall into some helpless-hopeless state. Without work people lose their way. They have less structure in their lives, less fulfilment, less social life and support. We have to get this country up and running again, and the economy prospering, otherwise we shall have many more suicides, depression and poverty. That would be tragic. We need to lead ourselves away from this future.

Any entrepreneur will tell you that you have to be an optimist to make a company successful. As a country we now need to learn to be more optimistic again, ditch the self-flagellation and galvanise ourselves into action to take a few risks, return to work, start new enterprises. Don’t buy into the criticism and negativity. It is up to us, our aspiration and our effort.

I have been re-reading a book by Dr Joseph Murphy called The Power of the Subconscious Mind. In it the author argues that it is essential to feed one’s subconscious with the positive images and thoughts of the goals one wants to achieve. Our thoughts are like seeds being planted in the soil of the future and if we plant negative ideas that is what we shall reap. He also describes the conscious mind as being the captain of the ship, telling the subconscious what to do, where to go. I have witnessed this in my work. It works, for without a sense of direction we wallow in confusion and go round in circles. We need a vision to strive towards.

Gratitude goes a long way in this endeavour. Let’s notice and talk about what is working rather than what isn’t. Let’s not create villains or victims. It doesn’t help us feel good or become economically prosperous. We need to think, talk and describe the potential of the UK in positive terms. We need to get out of the habit of talking critically about everything that happens here. It isn’t about pretending there isn’t room for improvement. Of course there is. But we must see that there is a way to cooperate and make things better.

So let’s give ourselves a break! In every country there are those who suffer and those who thrive. To enable more people to thrive, here and around the world, where others with less support than we have and depend on our success, we have to unite and believe in ourselves.

Sep 22

2020

7 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

The Coronavirus crisis has raised some of the deepest questions we humans ever face: what is the value of life? Is quality of life more important than length of life? What is the meaning to us personally of our lives? What gives us meaning, a sense of wellbeing, a sense of purpose? These are big questions and we very often are too busy to give them adequate consideration but this virus and all it signifies in terms of the limits it is making on our lives, makes us reflect on these big questions, doesn’t it?

Aged 70 now I look back and ask myself what has given my life the most meaning and the greatest sense of love and fulfilment? Work, sure, but at the heart of it are my sons and now my grandchildren. The love and joy I feel when I am with them and hear their news, the pain I feel when they are struggling, is what, for me, life is all about. Deep connection and care about what happens to them, their wives and their children. This is far more important to me, at this stage of my life, than my own life. They are the future.

Certainly I want to be around for them and to watch the grandchildren grow but I think there are many of my generation who do not want our children’s lives and livelihoods to be sabotaged by trying to shield us oldies. The hardship that will occur if there are further lockdowns will be financial and emotional, both here and in the rest of the world, as we are all so inter-connected these days.

And if regulations prevent me from seeing my children and grandchildren, siblings, cousins and close friends, then what is life worth? And for those poor souls who are sitting alone in care homes without their family to visit, without live entertainment to spark their minds and memories, what purpose each new day just for the sake of breathing and being a living entity if that living entity has no joy or purpose?

I am fed up with this “don’t kill Granny” thing. I would rather be killed by spending an extra day with my grandchildren than live for months on end without them and, who knows, maybe die of something completely different in that time period anyway? There are no guarantees in life in this situation or any other. I know a friend who doesn’t dare hug his young grandson in case that grandson gives him coronavirus and then has the burden of his grandfather’s death on his shoulders for the rest of his life. Could we grandparents not write a letter to our children and grandchildren stating clearly that we are of sound mind, understand the risks and consequences, and choose to be with and hug our family on our own volition because life isn’t worth living if one cannot do so, therefore removing any potential guilt from those we love?

Yes, we are supposed to be protecting others and the NHS but perhaps we could also elect simply to stay to die at home? That may sound brutal but a non-life may not be worth living. Those who do feel vulnerable then could themselves just stay at home and keep out of harm’s way. These are choices we need to consider. The anti-social behaviours we then witness in people deliberately spitting or coughing on others should be punished harshly for that is intentionally seeking to harm another, which is quite different.

Some elderly people are making the point that this situation is worse than the war. Although there were bombs dropping and one’s loved one might be away fighting, one could at least hug those who were there. One could enjoy a laugh and a drink with friends or family. Theatre and song carried on. One didn’t have to view other people or one’s neighbours as potentially lethal company.

Is death itself so frightening if life loses its purpose? I personally don’t think so. I have now been with three people on the moment of death, my baby son, aged 9 weeks, who died of a cot death, my father, and my mother. These transitions from life are extraordinary and I feel privileged to have been present in them, despite the pain they caused. In that moment, the person one knew leaves us and one is only left with the inanimate body, and one’s grief. There are so many myths and religious narratives about life after death that we can become muddled I think, for no-one can prove what it will be like. May it not just be a big sleep, perhaps, putting us out of pain, and therefore not so very bad?

We are listening to endless ‘science’ and medical advice but the advice is polarised into those who argue that this virus is not such a dangerous disease for the majority of people and we should seek herd immunity and those who argue for a focus on risk, fear and lockdown, whatever the ‘collateral damage’. Just as in many other areas of life, whether medical, legal, economic, the experts can differ in their analysis. Doctors are human and there are fads and fashions in medicine as in any other area of life. My baby son died for being on his stomach, which was the erroneous advice of the 1970s, based on research that had little to do with infants. As soon as this was recognised and babies were put on their backs, the number of cot deaths reduced. We need to heed the science but at the same time be aware that they can get things wrong. There is far more uncertainty in this world than they like to let on.

Old age is full of conundrums. We are supposed to be happy to do nothing in retirement, to rest after a lifetime’s toil. But this isn’t always the answer. My father was managing director of a cork company one day and retired the next. Sadly he found little to exercise his mind and interest in retirement and died only a few years afterwards, as many others did in those circumstances. Our immune systems respond to being engaged in life, and the sense of wellbeing and fulfilment this gives us. Luckily today, men and women who retire are finding many areas of interest through part-time or voluntary work, or even jumping out of planes for charity, and these keep them alive. Literally. Yes, the pull towards activity, whether it is climbing a mountain, sailing the Atlantic solo, pot-holing and other risky endeavours is endemic in us. If we became totally averse to risk, to the idea, as has been expressed, that ‘one death is a death too many’, then we would ban tobacco, alcohol, skiing, horse-riding, cars, bikes and more, and then one might well question what is the point of life? We live with risk every day. It’s a part of living.

We already know that there is a big increase in non-covid deaths. There will be an increase in mental illness too if we insist on keeping people in fear and isolation, in care homes, mental institutions, hospitals and prisons. There will be untold suffering if thousands of people become unemployed. I doubt any one of us would wish to be the person making these difficult decisions but I hope that the men at the top of our government – and I still assert there are not enough women’s voices at the top – will think in broader terms and understand that humanity has been lacking from the policies and practices we have so far experienced, where young and old die without their families being there to hold their hand.

Listen, if you can, to Dear Life by Dr Rachel Clarke which is being serialised on BBC Radio 4 at 9.45 every morning this week, to hear about the essential nature of compassion and humanity needed within medical practice. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000msx0 . And read my nephew Dominic Cavendish’s moving article about the importance of live entertainment in care homes where those deprived of faculties and families nonetheless come to life when they can sing. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/theatre/what-to-see/live-music-can-save-care-homes/

When I look back on my life, some of the happiest times have been in doing the simplest things – playing French cricket in the garden, or Monopoly by the fire, with my parents and siblings, going for a walk with my sons and grandchildren, sitting watching tv as a family or, now, cosy nights watching box sets with David. Yes, I had pleasure from travel, or (dangerous!) from galloping my horse across the New Forest, and huge fulfilment from my work as a coach and trainer but things outside the home – whether work or other activities, were never as enjoyable if there was discord or sadness within the home. The harmony and connection I received within the family always coloured everything else I ever did, and still does.

We are social beings, our sense of self shaped by family and friends. Deprived of touch, love and contact we wither. We also need nature in its glory to remind us that life is worth living. People in care homes are currently potentially being denied all those. So let’s adjust to uncertainty and risk, which is the true nature of life. Let’s try to find a way to get through these next few months by being mindful of the health of others but at the same time maintaining contact with those we love, and by continuing to do the things we love, so we know the value of life and, at the same time, are not so fearful of death.

Sep 01

2020

0

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

Are business leaders really thinking of the long-term business and emotional consequences of their staff permanently working from home? It may have been a delight for some people not to have to commute and to spend time at home but for others it has been lonely and isolating. We have had an exceptional spring and summer: how will it feel once the English winter of grey clouds, cold and rain arrives, I wonder?

Many years ago I was on the Committee of the Work-Life Balance Trust. Our aim was to get work-life balance, flexible working, job shares and home-working on the agenda of Government and business. We did a pretty good job and since that time, back in 2002, work life has transformed in many ways and working options are far more readily accessible than they were then.

But the point of the changes we were lobbying for was to enable people to have autonomy over their lives and flexibility to manage family, work and life in a more manageable way. We were not suggesting that companies enforce home-working on their staff and whilst I accept and understand that we needed to do this during lockdown I am concerned at the tendency for organisations to now demand that all or most of their staff continue to work from home.

Home-working suits some people more than others. Those at the top of businesses and therefore making these decisions are no doubt living in pleasant houses in nice surroundings and are likely to be – though not always – in settled relationships with children either at home or who have left home. They are also at the top of their game whereas those they manage are on a career ladder, which is far harder to climb without access to the hubbub of an office or shared space.

I’d like these leaders to give a little thought to those who are living in cramped apartments without much personal space, or having to stay with their parents longer than they might otherwise have done, or are in a flat-share where the other person is also home-working and potentially talking too loudly on their phones, or interrupting.

They may have young children, toddlers, babies, making a noise and demanding their time. I know quite a few stressed parents who have had to work well into the early hours of the morning after having to supervise their young children during the day. People can do this for a short time but a loss of sleep does little for cognitive capacity or the immune system in the long term.

There are those who are extravert who love to spend time with people and can’t, so have to make more of an effort to create their social life outside the office. Or an introvert who too easily becomes a hermit. Or someone living with an abusive partner who used to get some relief and support from going to an office and now is stuck in hell.

Some people can manage the discipline of a home-working day, others get distracted and pet the cat or fill the washing-machine. The environment of an office gives people structure, routine, a sense of purpose and contribution, whether this is in the public or private sector, a doctor’s surgery or factory.

Many of my generation and our children met their spouses at work – you spent time together, had much in common and ended up falling in love. Much harder to do that from the isolation of a flat, Tinder or no Tinder. So how easy will it be for young people to forge new relationships and meet their future spouse? These young are sitting at home behind a screen all day with hormones raging and no place to go – not surprising we are having all these illegal raves!

Then there is all that you are missing that can enhance your career – watching how your bosses comport themselves in the office with their fellow senior managers, with their direct reports, with clients. One can learn so much from just watching people walk about an office, or hearing how they discuss a business project on the telephone.

How will a boss ‘spot’ the person who has talent beyond what they are currently doing? It is so often that one perceives the hidden talent in others through a chance remark, or in observing how well they manage a particular situation. So much harder to do this when all you receive is emails or online output, only seeing the person physically via Zoom.

The creativity of a group of diverse people or diverse thinkers come to more innovative solutions than any one person on their own. Someone you bump into in the corridor or chat a problem over with on the other side of the desk can often have the answer to a challenge, or the information you require. They can share with you what has worked or not worked, inform of best practice whatever kind of organisation you work in.

There are meetings – often thoroughly tedious and unproductive, perhaps, but one does learn how to chair, how to speak up with an idea, how to listen, and can gain the cross-fertilization of information from other departments. And the banter that lightens the discussion can often bring a negotiation to a close more easily than plodding through a process in the sterile world of online meetings. Plus the fact that many deals are done at the coffee break, and that you forge social and business relationships with colleagues who can remain an important part of your networking circle for the rest of your life.

Yes, I know all this can be done on Zoom or Microsoft Teams or whatever but it is just not the same. I remember some of our clients discussing flexible working many years ago and remarking that one had to be careful that people didn’t go ‘native’ – that meant that they almost forgot who they were working for, lost that sense of pride or belonging. The solution was to make sure they came into the office frequently enough to bond and remember the organisation, product or service they were representing.

Of course, people can save themselves from the ordeal of commuting. I remember some of my clients leaving home regularly at 4.30am and not returning until after 8pm. Too long a day. But now the trains and tubes are empty and all those small businesses that relied on the working population for their income will go bust. And if the economy goes bust we all suffer – and not just us, people all over the world who may supply the goods from India, South America or the Far East, could face poverty. People suggest that the provincial cities may revive as a result of these changes but if everyone is stuck away on their computers all day there is no great reason for this to happen. We have to get out and about.

And what does all that sedentary computer time do to our bodies and brains, I wonder? Our brains are plastic. They alter literally every day as we think or adapt to new tasks or ways of working or living. Habituating to seeing people through a screen rather than in real life is bound to change our perceptions, limit our social and emotional intelligence, potentially also our empathy. We are detached, possibly less able to pick up those intuitive messages that you gain from a tiny cue of body language, tone of voice, eye movement, that gives away how the other person is feeling or what they are planning. So much harder to do this through a screen. And as for our physical health, many people had gyms within their office space and would use them before or after work or in their lunch break. This could possibly be harder to find, and more expensive, where they live.

Wonderful to have flexible working, to be able to work from home for part of the week. But it needs to be a choice and something that is negotiated by a manager and their team individually. This blanket decision that some organisations are making that everyone should now work from home does not make financial sense as far as the nation’s economy is concerned. It does not make social or emotional sense and it cannot make sense with regards to personal growth, team development and the nurturing of individual and organisational enterprise. For the majority of people this virus is not deadly but certainly those who are vulnerable can choose to shield at home, or wear masks, gloves, visors, but for the rest of us reasonably healthy folk let’s get back to the fray and try to reboot our economy, otherwise we shall all suffer.

Aug 14

2020

4 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

The NHS is, of course, of great benefit and value in our country and does amazing work. Near miracles are performed every day. We have leading edge processes and first-class front-line workers but nonetheless many patients are being short-changed within a system that does not function in a coordinated or compassionate way. It is failing us.

As you know, David has Parkinson’s Disease, and alongside this many other of the uncomfortable and disturbing symptoms that interrupt quality of life as we get older. It breaks my heart to see the endless flow of NHS appointment letters arrive on his desk, some with appointments for high blood pressure (a dangerous condition) for September 2021 (surely you cannot justify a wait of a year?), others giving him a ‘pre-assessment appointment’ after the date of the process for which he is supposed to be having that pre-assessment. It is cruel, as he has to spend so much time then trying to rearrange said appointments, or chasing up results, but only getting through to robotic administrative staff who say they don’t have the papers, or can’t help him.

He feels alone and lost within a system that does not function as it should, nor care. And how many others around the country are in similar situations, many of them, like David, with serious conditions that require action? I suspect very many. Each department seems to operate in a vacuum, as if one part of our body does not relate to another. I have listened for many years now to David making calls to some NHS department or another and getting either no reply (endless ringing tone or musac) or the monotone voice of some administrator who, quite frankly, seems to care nothing for his wellbeing. “I don’t have those records … It’s not my responsibility … you will have to ring x department…” and so the merry-go-round goes in circles again. And, in the meantime, David becomes exhausted and despondent.

So who is eventually accountable? All one hears from those who work within the NHS is that they are powerless and victimised and it’s all the Government’s fault, whichever party is in power. As some nurses shared on a workshop we ran many years ago now, when asked what they were good at they replied “we are very good at moaning”. But that doesn’t improve things unless those working within the NHS come up with solutions and make change happen. After all, if some GP surgeries perform really well for their patients, so can other GP surgeries. If one hospital can function well, so can another. It is about leadership, coordination and willpower to make change happen for the benefit of patients.

But the NHS is a sacred cow. We can’t say anything about it without looking thoroughly disloyal, a traitor to the cause. But, I am sorry, we cannot maintain the effectiveness of any organisation or process if we are not willing to analyse – and there is a difference between analysis and criticism – and work out how to do things better.

The UK has experienced a large number of deaths and a large number of excess deaths during this Covid period. It is hardly surprising when it is just about impossible to get to see a doctor. There is no-one there for us. One almost has to bash a door down to get to have any kind of physical diagnosis of a problem that cannot be diagnosed over the telephone. Many people don’t like to make a fuss. Others don’t even realise you can make a fuss or change an appointment that has been issued a year in advance. So people will be left ill and dying at home, feeling isolated and alone, with no-one there to help them. We can’t accept this.

Even in our supposedly world-class hospitals a friend of mine has recently had appalling treatment, told she had a fracture in her left thigh followed by a phone call several days later to say that oh no the fracture was actually in her right thigh, followed by a phone call several days after that to tell her that woops there isn’t a fracture at all and the radiographer reading the scan had made a mistake. Another was told they could go off blood-thinning medication that was actually crucial to him staying alive. Yet no-one seems accountable and the stress and anxiety such mistakes cause is certainly detrimental to people’s health. These problems also add to the huge cost of medical errors and claims.

But sadly one rarely feels ‘held’ by a consultant within the NHS system these days. Young women have thoroughly lonely pregnancies, with no continuity of care, seeing different people each time, having to repeat endlessly – as David has to today – who they are, their histories and problems.

In David’s case he wasted a whole year of ill-health with no action due to lack of continuity of care. He saw five different doctors and only on the last occasion, after months of discomfort, was told that what had been proposed by the first doctor was actually contraindicated. This is a year during which his quality of life was severely interrupted.

Putting people in this isolated state of stress seriously depletes their immune system. For David or other elderly, chronically or severely ill patients to have to be shunted from one department to another, receive appointment letters that make no sense and then have to hang on the line all day not getting a result leaves them depleted, anxious and desperate. It just isn’t good enough. We need to say so and get something done.

Trying to make changes within the NHS is well-nigh impossible, though. It is an enormous and unwieldy organisation with such a huge workforce that makes it almost unmanageable. Over the years I have known many thoroughly competent management consultants and change agents who have tried, over many decades, to tighten up what has been a failing system for years but without success. The NHS is happy to pay ridiculous quantities of money to the major management consultancies and then, having ticked that box, just put the report on a shelf and do nothing about it.

The Government has stipulated that all patients over 75 should have a named doctor but some of today’s GPs don’t seem to buy into continuity of care, or whole-person care. They don’t seem wish to follow in the footsteps of the old-fashioned family doctor, as David himself practised, where you felt one person knew you, your family, your home, and your ailments and would hold you through these periods of sickness.

With today’s technology, patients should be able to hold their own records and all NHS departments should have access to all records at all times. It should be dead simple. But the Trusts operate like little empires, getting financially rewarded for logging each individual episode. This is not good value for money for taxpayers and needs to be radically overhauled. It’s not fit for purpose.

People will surely die prematurely within a fragmented service, especially now that the sole focus seems to be on Covid-19. We need to wake up and start to remember that people have a whole variety of ailments that require attention and that the system needs to care as much for the emotional wellbeing of patients as the physical because each impacts the other.

To have a healthy population we need an NHS that has lines of communication and accountability that are far better than they are at present. If anyone has solutions or ideas about how to improve these systems please share, or write to your MP, or do something because it really is breaking my heart to watch David struggle through this every day.